Hope in early medieval canon law

While the dark clouds of uninformed, misguided higher education policy are gathering over universities in the Netherlands, I was asked to talk about hope in early medieval canon law for the International Medieval Conference (IMC) at Leeds this year. The confusion did not end there: canon law—with its flurry of prohibitions, penance, and anathemas—does not strike one as a textual genre in which hope is a central feature. Yet, there is more than meets the eye. In fact, I should like to argue in the course of this paper that canon law is the literary genre of hope par excellence.

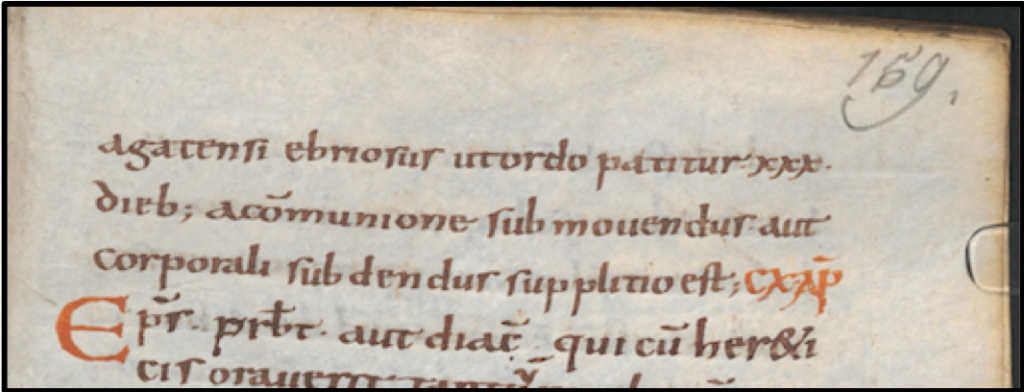

Collection in 400 chapters, c. 109

Vienna, ÖNB lat. 522, f. 159r

In a way, this statement is perhaps a tautology: in many respects, the act of writing, of producing something for future readers is always a testimony of hope. In an early call to human scientists to put emotions front and centre in their studies, Thomas Meisenhelder in 1982 defined hope as a particularly active emotion; one ‘which includes the sure recognition of the future’s uncertainty’, but still ‘continues to actively confront the future as if one’s actions had effective meaning’. Hope can then be contrasted with the passive endurance of an unalterable future. In a particularly moving description, Meisenhelder describes the hopeless person as one who ‘accepts the inevitability of his or her singular life and lonely death’. In contrast, the hopeful denies one’s finite aloneness and actively confront the two basic facts of life: loneliness and death.1

Viewed as such, the activity of writing down religious and ecclesiastical rules is a prominently hopeful act. The aim of the compilers was, one assumes, to cleanse society—and future societies—of disruptive behaviour and to help people alter their lives to accord better with an ideal, Christian future. This would be a particularly ‘big hope’, in the scheme proposed by Peter Burke, in a recent article titled ‘Does Hope Have a History?’ (the answer is, thankfully, ‘yes’). He distinguished the various objects of hope in ‘big hopes’ on the one hand (hopes for a better world, for the entire human race) and ‘small hopes’ (individual hopes, everyday hopes).2

The prefaces to canonical collections, one could argue, communicate the ‘smaller hopes’ of the compilers, i.e. the aims which they hope their specific collection serves to accomplish, but also refer to that ‘bigger hope’, the one concerning humankind. Dionysius Exiguus, the compiler of the Dionysiana, is clear about the end goal of canonical law in general, when he observes that the ‘discipline of ecclesiastical order, remaining invulnerable, might offer to all Christians a gateway for gaining the eternal prize.’ The latter Collectio Sanblasiana adopts the same preface.