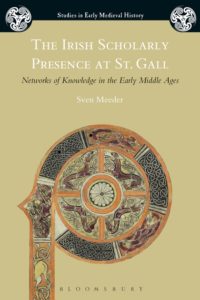

April saw the publication of my book on the Irish scholarly presence at St. Gall with Bloomsbury Academic publishers. The cover is certainly wonderful and I can only hope that the reviewers feel that the content matches it. To give you some idea of the argument of the book, I am including the final version of the brief conclusion of the book here.

April saw the publication of my book on the Irish scholarly presence at St. Gall with Bloomsbury Academic publishers. The cover is certainly wonderful and I can only hope that the reviewers feel that the content matches it. To give you some idea of the argument of the book, I am including the final version of the brief conclusion of the book here.

The glosses that were added to the breviary of St. Gall’s books in the last decades of the ninth century are testimony to the voracity with which the community had obtained its scholarship. In their urge to acquire learned texts, the monks of St. Gall had hit a number of misses, so the later annotator recorded. Especially among the texts of purported patristic writers, he found false, mendacious and useless works. While the later annotator appears to have had the leisure to thoroughly examine the books in the library, the earlier copyists and book buyers were simply too eager to collect authoritative texts and too time-pressed to inspect closely what they were about to acquire.

These unique glosses paint a picture of a bustling and vibrant blooming of intellectual energy that distinguished the Carolingian revival of learning. Networks of knowledge were buzzing with activity and scholarly exchange. With its focus (mainly) on a few manuscripts, written at or brought to the Alpine monastery of St. Gall, and containing scholarly material originally composed in Ireland, this book only covers a tiny detail of the prodigious intellectual phenomenon that was the Carolingian revival of learning. Nevertheless, this study represents an attempt to offer a contribution towards a better understanding of the intellectual boom of the eighth and ninth centuries. Rather than taking a top-down approach and attempting to explain the situation ‘on the ground’ from the well-expressed ambitions of a distant court, it aims to present a ‘horizontal’ model for the enquiry of intellectual contacts between St. Gall and other learned centres. And despite its modest scope, this book has tried to demonstrate that, when studied closely, a history painted with broad strokes can prove to be deceiving. Thus, whereas the numerous surviving products of Irish learning in the library of a monastery with an Irish patron saint would suggest the existence of a singular connection between the monastery and Irish scholarship, or a gateway function connecting Ireland with continental Europe, a more detailed look presents us with a different picture altogether.

The turbulent and creative years of Carolingian renovatio formed the circumstances in which Irish learning was spread over the continent, where they were read, copied, redacted or ransacked with vigorous creativity. The community of St. Gall managed to collect a sizeable corpus of Irish scholarly works with some of the most influential texts from Ireland: De XII Abusiuis, the Collectio canonum Hibernensis, Ailerán’s exegesis and Irish penitentials. The monastery was no stranger to Irish influence. It appears that a modest, but steady stream of pilgrims visited Saint Gallus’s grave among the many travellers seeking to cross the Alps into or out of Italy.

The Irish learned texts were, however, obtained through other channels. The study of the extant manuscript witnesses to Hiberno-Latin scholarly texts at St. Gall reveals evidence (sometimes circumstantial) for intellectual connections with nearer, continental centres. Especially north-eastern France and central and southern Germany – and of course Reichenau – seem to have supplied St. Gall with Irish scholarship; and vice versa. By the time it arrived at the monastery of St. Gall, it had often already gone through a number of continental or Anglo-Saxon hands: an Anglo-Saxon by the name of Eadberct had been able to put his stamp on a version of the Hibernensis; De XII Abusiuis was already employed to fulfil a role in a continental, political dispute; the preface to Cummean’s penitential was already appropriated for use in a continental penitential composition.

The monastery of St. Gall did not fulfil the role of bridgehead, connecting Ireland with the continent, nor was it any more of a gateway than other continental centres within the Frankish realms. If metaphors are necessary, St. Gall acted more as a sink strainer. With the streams of scholarship rushing through St. Gall, an impressive number of Irish works were trapped by its monks in their nets. Partly thanks to the cupidity of the St. Gall monks, partly owing to its convenient location, and partly due to the fortuitous survival of so much of the library’s holding, we have this unique collection to study.

None of this, of course, diminishes any of the creative splendour of the Irish scholars who produced the learned masterpieces. On the contrary, the rich evidence of continental appreciation and appropriation, and the dynamic redistribution of Hiberno-Latin scholarship between continental intellectual centres only underlines the fact that Irish learning was valued greatly by its continental recipients for its skill, sagacity and utility. It was these qualities rather than any value automatically attributed to ‘Irishness’ that ensured its place within the pan-European pool of learning.

The medieval spread and reception of scholarship was, ultimately, an exercise in cultural exchange in which both the ‘sender’ and the receiving party influenced the scholarly product that was shared. The transference of a cultural object from one context into another by necessity transforms its meaning. By the time Irish scholarly works arrived at St. Gall, they had already gone through a number of such semantic transformations. While the Irish background is important for historians to understand the context of the works’ conception and original composition, we cannot assume that this background was equally significant for the St. Gall recipients. In fact, one can justifiably wonder whether the St. Gall monks always knew the origin of the Irish texts they copied, read and taught (and whether they cared). Similarly, the meaning and relevance of Irish works of learning must have been different for the community of a continental monastery than for its Irish author and initial Irish audience. In fact, one could argue that the Irish scholarship became ‘more continental’ (or rather ‘more European’) with every step of its dissemination beyond the shores of Ireland. This ‘globalizing’ trend is, after all, the hallmark of the most durable of scholarly expressions. And the durability of Irish learning is not in doubt.