2021 will be the year in which my two-year project ‘A Living Law’ starts in earnest. Funded by a research scholarship from the Gerda Henkel Foundation, the project commences in May 2021. The project aims to shed light on the work of the early medieval scholars involved in the compilation of small, ‘minor’ canonical collections.

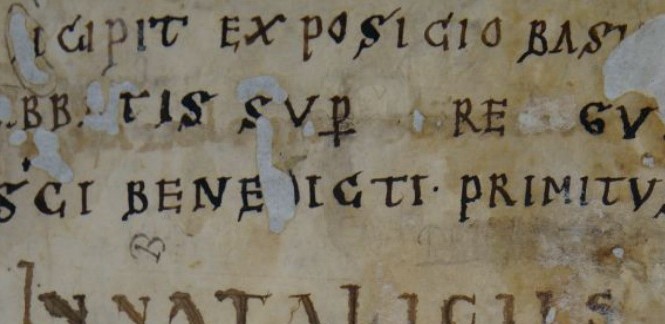

http://www.e-codices.ch/de/csg/0679/156

Recent years have seen some work on these smaller, ‘unstructured’ collections of limited, mostly local impact, but relative to the important academic advances in the study a number of important, widely-circulated canonical collections (think of the new edition of the Hibernensis, and the project chronicled on pseudoisidor.mgh.de), these works are somewhat overlooked. I want to focus on the canonical dynamism on a more quotidian level, which latches on other current historical research into the Carolingian period, which has come to realise that the creative energy sustaining the revival of learning was fostered in more local, personal, and institutional settings and was not the direct result of a court imposing its agenda on its subjects (think of the important studies on local priests).

The following texts will be my initial focus:

| Collection | date and place [Kéry, 1999] | mss | edition | |

| 1 | Collectio Burgundiana1 | s. viiiin, N-France | 1 | none |

| 2 | Collectio Sangermanensis3, 4 | s. viii, Gaul | 9 | yes |

| 3 | Collectio Frisingensis secunda2 | s. viii2/2, Lake Constance? | 1 | yes |

| 4 | Collectio 250 capitulorum3 + Sangermanensis abridgement | s. viii2/2, N-France? | 3+1 | none |

| 5 | Lex Romana canonice compta2 | s. ixmed, Italy | 1 | yes |

| 6 | Collectio 400 capitulorum1 | s. viii2/2, N-France, Rhineland | 3 | yes |

| 7 | Collection of Laon 201 and St. Petersburg Q.v.II.54 | s. viii2/4-med, Cambrai or region | 2 | partial |

| 8 | Collectio of Vat. lat. 68081 | s. viii-ix, Farfa? | 1 | none |

| 9 | Excerpta Bobiensia2 | s. viiimed-ix, N-Italy | 2 | yes |

| 10 | Collectio 309 capitulorum2 | s. viiimed-ix, place unknown | 1 | partial |

| 11 | Collectio 91 capitulorum1 | 800-820, Gaul? | 1 | partial |

| 12 | Collectio 53 titulorum | s. ix?, France | 3 | none |

| 13 | Collecto Bonaevallensis prima2 | s. ix1/3-3/4, Bonneval? | 1 | partial |

Qualifications in Kéry, 1999:

1 ‘unstructured collection’

2 ‘(small) systematic collection’

3 ‘derivative collection’

4 ‘excerpts’